In Tavarnelle Val di Pesa, a small town in the famous wine area Chianti, I park my car to visit the wood carving workshop of Filippo Romagnoli. From the outside, the building looks like a normal family house in a residential neighbourhood. The workshop is on the ground floor, and Filippo’s family lives above. When you enter the first room, you notice wooden frames and candelabra that hang on the workshop’s walls. Large shelves are packed with wood and carving projects in various stages. A big table stands in the middle of the room. On the table lay refined wooden rolling pines, beautiful cutting boards, and pasta stamps. The stamps are still waiting for their final finish. Bright sun beams illuminate the carving table on the right side of the room. It must carry about a hundred little carving tools from Italy, England, and Germany, among other places. The producers of these specialised tools are small artisanal businesses as well. Next to the carving table stand two delightful little lemon trees that have found refuge inside from the colder winter days. The second room of Filippo’s workshop is filled with bigger tools that he uses for the initial carving stages of his wooden products. Planks of different types of woods are leaning on the wall, waiting to be transformed. The workshop’s atmosphere is calm, and warm wood dust flies peacefully through the air.

Filippo Romagnoli is the third generation of a Tuscan family of wood carvers. His grandfather Ferrando learned how to carve wood at the age of 11. In 1918, he joined a workshop in the artisan neighbourhood in Florence named San Frediano. At the time, Florence was one of the most important cities for wood carving in Italy. The city was filled with Renaissance-like workshops, the so-called “bottega”. These workshops were places of teaching and learning and collaborative work. A wider network of workshops ensured the excellence of craftsmanship in the city. If a student was very good at designing but less skilled at wood carving, the master would put him in contact with workshops of a different craft. This supportive structure allowed students to maximise their talents. Reflecting on the bottega’s communal organisation and with a critical view on today’s individualisation of artistic genius, Filippo explains: “there is no one-man dance in art”.

At the bottega, apprentices would start at a young age to learn the craft and responsible work behaviour. Filippo shares with a twinkle: “at 11, they’re very smart, at 12, a bit less.” The learning process was long and slow, the weeks filled with hard work. A crucial point of the young wood carver’s education was understanding that similar shapes may occupy different meanings. For instance, the numbers 6 and 9 have the same shape but symbolise different quantities. One defined form possesses a broad expressive quality. To project this kind of knowledge onto a three-dimensional object and to plan and play with its effects was challenging: “It’s like a rebirth.”

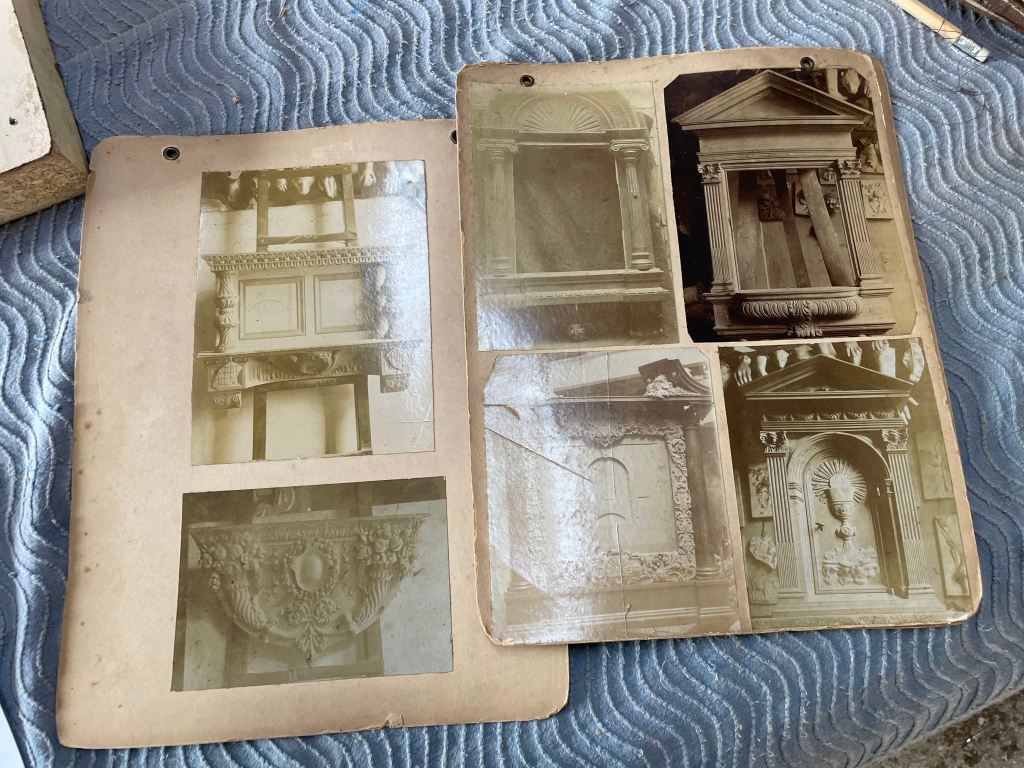

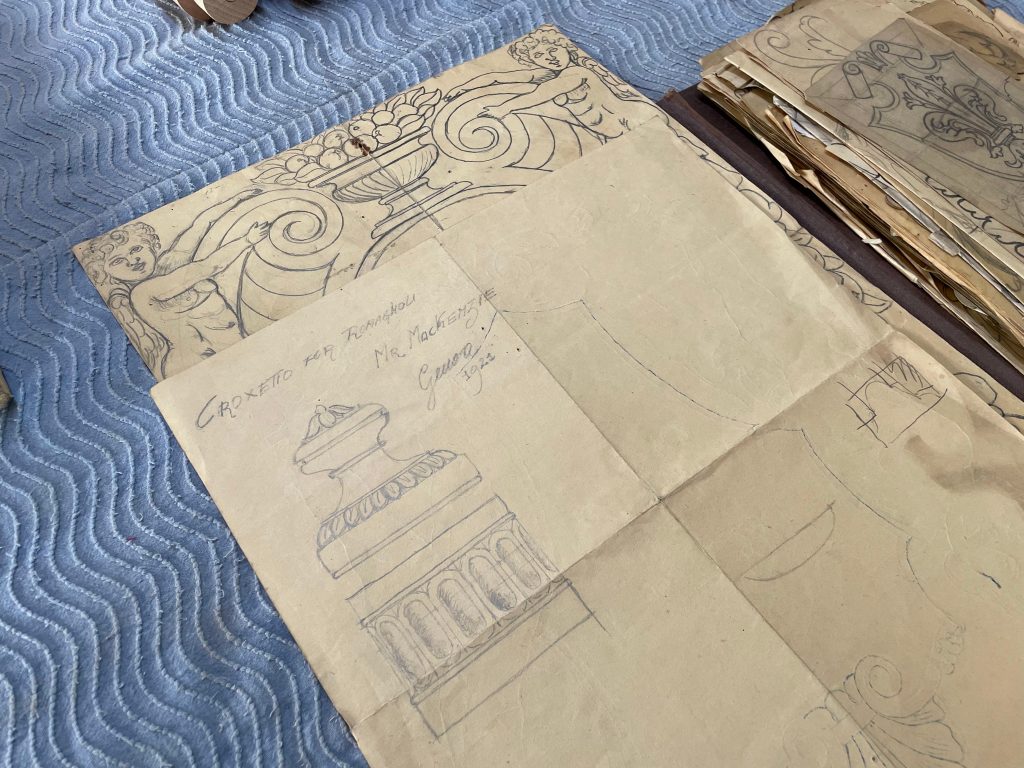

Filippo’s grandfather was trained at the workshop of master Giulio Campolmi. It was located at the Via Santa Maria in San Frediano, near the Teatro Goldoni. The workshop represented a novelty of industrialisation—Campolmi was paid by bigger factories to train apprentices to eventually become their employees. He collaborated with many famous architects at the time, which gave his students the chance to work on more advanced and intricate projects. In the early 1920s, an architect who rehabilitated an old castle in Genoa brought pasta stamps to Campolmi and asked for their restoration. The apprentices were laughing at this curious object, since they usually worked on larger pieces. However, this marked the moment when Filippo’s grandfather began to carve pasta stamps. A hundred years later, the family tradition of carving pasta stamps lives on in Filippo’s workshop.

Romagnoli pasta stamps are tools to make Corzetti. Corzetti is a type of round, flat pasta, resembling a large coin. One side of the Corzetti shows an intricate design while the other displays a simple pattern. The decoration allows for a beautiful individualisation of the pasta. It also enables the sauce to better hold on to it. Corzetti come from North-East Liguria and date back to the Mediaeval Period. Nowadays, Corzetti are difficult to find. Since the profession of wood carvers is slowly disappearing, fewer and fewer pasta stamps are available to buy: “I found Italians had totally forgotten this item.” The wood-carved stamps, however, are vital to making the pasta. Filippo explains: “We’re part of the ingredients.”

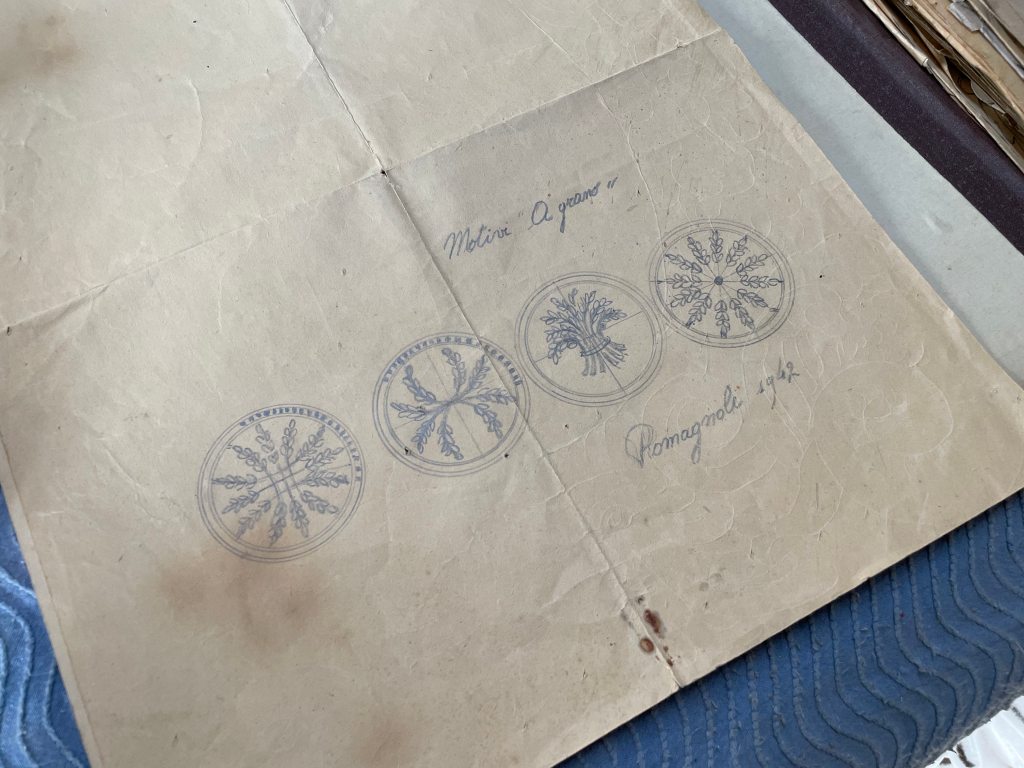

The Corzetti pasta stamp is a beautiful and very specialised kitchen tool. It consists of two parts. The lower part has a sharp edge to cut the rolled out pasta dough into round shapes. To create the decorations on the Corzetti, the round pasta disc is pressed between the two parts that have engraving imprints. Filippo carves the Corzetti stamps out of beechwood from the Casentino forest between Florence and Arezzo. The Casentino forest is a stony territory. The wood grows slowly, rendering it very solid. One cubic metre of Casentino beech wood weighs about 1200kg, making it much heavier than, e.g., beech wood from the German Black Forest. The high density is particularly important to stabilise the stamp’s cutting edge which is its most fragile part. The wood’s sturdiness is also essential to maintain the shape of the imprint. Filippo’s pasta stamps come with a range of different motifs; the Florentine lily, the bee, and an octopus, among others. Customers can also contact him for individualised designs.

When Filippo wondered how to carry his profession into the 21st century and the world of e-commerce, he found a market niche for pasta stamps. Especially American clients were interested in his work. Now, they make up his largest group of clients, followed by Australians and Brits. Filippo sells his pasta stamps, rolling pins, and cutting boards on Etsy, a platform that aims to sustain small creative businesses. This is not an easy task. The first difficulty lies in the fast process of making online purchases which stand in stark contrast to the slow process of hand-carving the pasta stamps. Luckily, Filippo finds his clients to be understanding. The other difficulty relates to the bureaucracy of shipping. His products have to fulfil tight and extensive regulations since they come into contact with food. The many certifications he has to provide keep Filippo occupied and take away essential carving time. He is very critical of how Italian and European bureaucracy burdens artisans who do not have the human resources to keep up with the paper work: “How can you make it difficult for mini businesses?”

Filippo is also worried that young people won’t find the profession of the wood carver attractive anymore: “If you want to do something with your hands, it’s very, very difficult.” The bottega workshops have disappeared, the master-student relationship now mostly lives on within families. Filippo studied at an art institute in Florence and was taught how to carve wood by his father: “you learn the beauty and the hardness of the work”. He believes that current school education is too mind-focused and fails to connect intellectual knowledge and artisanal craftsmanship. Students are not encouraged to consider physical professions. He asks, “Where is the artist to connect mind and body?”

i don’t want to make it by machine. at least one in the world has to do it by hand.

While Filippo and I are chatting about the past, present, and future of wood carving, he shows me his workshop and explains the various steps of making the pasta stamps. In advance, I had placed an order for a pasta stamp with the Florentine motif. Filippo waited with the final carving to give me a life demonstration of his work. The stamp is clamped into the carving table, and Filippo begins to carve the miniature lilies. He then proceeds to make the gauges in the centre of the stamp. Every little petal in the middle requires three precise gauges. It is fascinating to watch him work, as he cheerfully describes all the intricate details to pay attention to. Finally, he covers the stamp with a thin layer of non-allergenic mineral oil to protect it from humidity.

The pasta stamp in my bag, I drive back to Florence to make Corzetti at home. I use the pasta dough recipe from the Romagnoli website, which works perfectly. The dough is firm enough to retain the imprint and not stick to the stamp. It is a pleasure to see my kitchen towel slowly filling up with beautiful Corzetti coins. Having the pasta prepared, I braise turnip greens with garlic, chili, and anchovies in olive oil. Once the turnip greens become soft, I use a stand mixer to turn everything into a brightly green and creamy pasta sauce. Mixed with the cooked pasta and topped with toasted pine nuts, I look with excitement at my first ever Corzetti dish.

Thinking about all the different layers of work involved, I eat each coin with care and attention. I wonder, if the client from Genova wouldn’t have contacted Filippo’s grandfather 100 years ago to restore pasta stamps, what would have happened to Corzetti? If Filippo weren’t dedicated to maintaining his family’s craft, would I have ever learned about Corzetti?

…

What will happen to this pasta that is so tightly intertwined with the fate of the wood carving profession?