With monumental buildings giving way to the dusty dominance of time, would you believe that the seed of a salad can survive centuries?

Traces of the past appear in many shapes. To reconstruct the realities of long-gone people and societies, historians and archaeologists usually seek to collect and contextualise written sources and objects. Yet, natural and man-made forces frequently eradicate even the most sturdy, massive structures. However, between all the dirt and crumbled stones, a grape pit or cereal grain may still lay intact, providing a window into the culinary traditions of a different time and place.

The archaeological study of old plant remains is called archaeobotany. Archaeobotanists analyse fruit and vegetable pits and seeds to better understand past societies’ cultural, culinary, and economic habits. Food consumption, after all, penetrates every layer of society. Every single person has to eat. Applying archaeobotany, therefore, can illuminate spaces sometimes overlooked—the small but busy storage room instead of the grand dinner table, the rubbish deposit instead of the foyer. Through an archaeobotanical analysis of food, according to Charlotte Molloy, one can generate “a more intimate, and truthful insight into how people were living.”

archaeobotany can give you so much about everyday life and ordinary life.

Charlotte Molloy is a practising archaeobotanist. We met at the University of Oxford, where we both completed our master’s degrees. Charlotte’s interest in classical studies and old empires began at the end of high school. She profoundly enjoyed reading Homer’s Odyssey and following Odysseus’ travels. Encouraged by her tutor, she decided to study Classics at Royal Holloway University in London. In her first year, Charlotte learned about ancient Greek and Roman history but was hesitant to explore archaeology: “I knew that Indiana Jones probably wasn’t a realistic representation of archaeology. I thought it was people with long beards and crazy jumpers.” She also felt that the profession wasn’t very welcoming for young women. She admits, “I couldn’t have been more wrong.”

When Charlotte encountered archaeobotany, she was fascinated by the possibility of investigating everyday culture through ancient diet. In her second year at university, Charlotte signed up for a course on Roman Britain, which included a session on food history with archaeologist Dr Lisa Lodwick. This session was eye-opening. Charlotte learned how much the food people ate—and the way that they ate it—could tell you about an individual or a culture. Employing archaeobotany, one could explore habits as small as a daily meal and spaces that are “not linked to these grand monumental gestures”, usually shaped by elite classes. Archaeobotany, she realised, has the potential to create a wider, more inclusive path into the past.

The summer she completed her undergraduate degree, Charlotte joined archaeologist Dr Erica Rowan on the Sardis excavation site in Turkey. For four weeks, Charlotte worked as Dr Rowen’s assistant. Under the burning sun, they studied plant samples from the early bronze age to the Byzantine period, spanning almost 3000 years of history: “With these samples, you can track food through millennia.” Charlotte came back to the Sardis excavation site the following summer. This time she could study plant remains from the late antique to late Roman period, from the 4th to the 6th century CE. Working in the field solidified Charlotte’s excitement for the profession—her path as an archaeobotanist was set.

how does archaeobotany work? how do archaeobotanists find, contextualise, and interpret tiny plant remains?

Plants can find their way into the archaeological record by four different ways. The most common way is through charring; after contact with fire, a carbon fossil of the hard parts of the plant—seeds and grains—are left behind. Imagine an accidental domestic fire or a natural disaster—these kinds of events often create charred plant remains. Plant remains can also be preserved by mineralisation; when they come into contact with substances like phosphate or calcium. To decay, plant matter needs moisture and oxygen. Take one of those away and it does not decay. Therefore, if a plant is left in an extremely arid environment, it can be preserved through desiccation. There exist astonishing examples of this process from the Amheida excavations in Egypt, where entire baskets full of dates have been found buried in the sands since the Roman period! At the other end of the scale, if the plant matter stays submerged in a waterlogged environment, it can also remain very well preserved. For instance, two iron age wells excavated in Silchester in England contained the waterlogged remains of the oldest coriander found in the country! When preserved through charring, mineralisation, desiccation, and waterlogging, it is astonishing how plants and their remains can survive for centuries.

Plant remains are found within soil samples—a so-called fill. After its excavation, the fill is processed to separate the plant remains from the soil. Processing either involves wet or dry sieving in the case of waterlogged or desiccated remains or flotation in the case of mineralised or carbonised remains. Because the carbon or mineralised remains are lighter than the soil that they are in, they will float to the top whilst the soil and rocks sink to the bottom when dropped in water and agitated. Separated from the soil, the plant remains will be dried and are ready for closer analysis with a microscope.

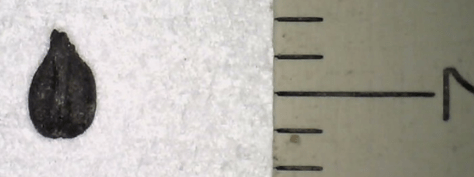

Although these are quite literally very small discoveries, as the mm scale in the picture illustrates, the excitement of recognising food and plants that are still common today is palpable for Charlotte: “I love finding grape pits because they look like the skulls in those wild west bars, the skull of buffalos […] it’s so cool.”

how do you analyse the plant remains? how much can you actually learn from a small grape pit?

Charlotte sees archaeobotany as “a way of communicating with ordinary people in the past”, seeing not just into their store cupboards but into their mindset. Plant remains can give astonishing insight into people’s culinary habits and their relation to their land. Archaeobotanists can trace what cereals people were consuming, how these cereals were stored, and where they were processed. For instance, “if a sample is particularly rich in just grains, the evidence leans toward cereal processing or agricultural processing. In contrast, if a sample has very few grains in comparison to how much charcoal there is you can infer that it is more likely that the grains were just windblown. If there is a very wild range of different types of food, edible food, and a lack of charcoal, it can be evidence of food storage.” Further, if there is a rare seed that one didn’t expect to occur in the specific area and time excavated, “you can track seed travelling”. Through food, archaeobotanists are able to study cultural and culinary habits of past societies with remarkable detail.

charlotte’s research: using archaeobotany to analyse roman houses

Charlotte uses archaeobotany to better understand how space was used in Roman houses. When it comes to these houses, there is a lot of space archaeologists tend not to analyse—spaces that are not grand dinner rooms or entrance halls. Charlotte intervenes: “wouldn’t it be interesting to use archaeobotany to figure out the use of these spaces?” One place she investigated was a house in Sardis, Turkey. This house had been destroyed by a fire in the early 7th century, leading to a rich amount of charred plant remains. Now the detective-job of the archaeobotanists begins. Charlotte explains to me that there was one room where many pots, pans, and pottery were found. Yet, there was no evidence of a former stove. She wondered, could it be a storage room? Or was it a kitchen, despite lacking traces of a stove? Looking at the archaeobotanical evidence, she found a high concentration and wide range of edible plants; olives, figs, nuts, barley, and peas, but no evidence of crop processing. That suggests that the activity being carried out in the room at the time of the fire was food preparation. She finally concluded that the room may have served as a kitchen.

As part of her research, Charlotte investigated another case study, a villa in Saglasos, built originally in the 2nd century CE. Archaeobotany could reveal that the estate was sub-divided and used for agricultural activities in the 6th century. In one room, excavators had found a press for mulberries and evidence for making mulberry jam. Another room showed evidence of grain threshing, a third room traces of burned rubbish, including food. Together with analyses of space, Charlotte summarises, “archaeobotany can help us to reveal and tease out those hidden histories that are told through food.” Asked where the most fruitful fills for archaeobotany are usually found, Charlotte responds: “You would be surprised about the amount of remains we find from toilets.”

it’s true. we are what we eat—it says so much about us, our personality, and our background.

How will future archaeobotanists reconstruct current culinary cultures? Chances are they will have a hard time. Food mobility, sewage systems, and genetic modifications of seeds will make it very challenging to formulate hypotheses on food cultivation and consumption. Just think about genetically modified seedless grapes. What should the archaeobotanists analyse under a microscope without any hard plant remains? To be honest, I now feel compelled to refrain from eating any more seedless grapes or tangerines. I want all these tiny seeds and pits to continue to defy the devastation of time, the angel of history. Half-joking, half-serious, Charlotte concludes, “The real shame about modern toilets is the u-bending of the flush […] all the modern archaeobotany is flushed into a sewer.”