Credits: Karina Klages

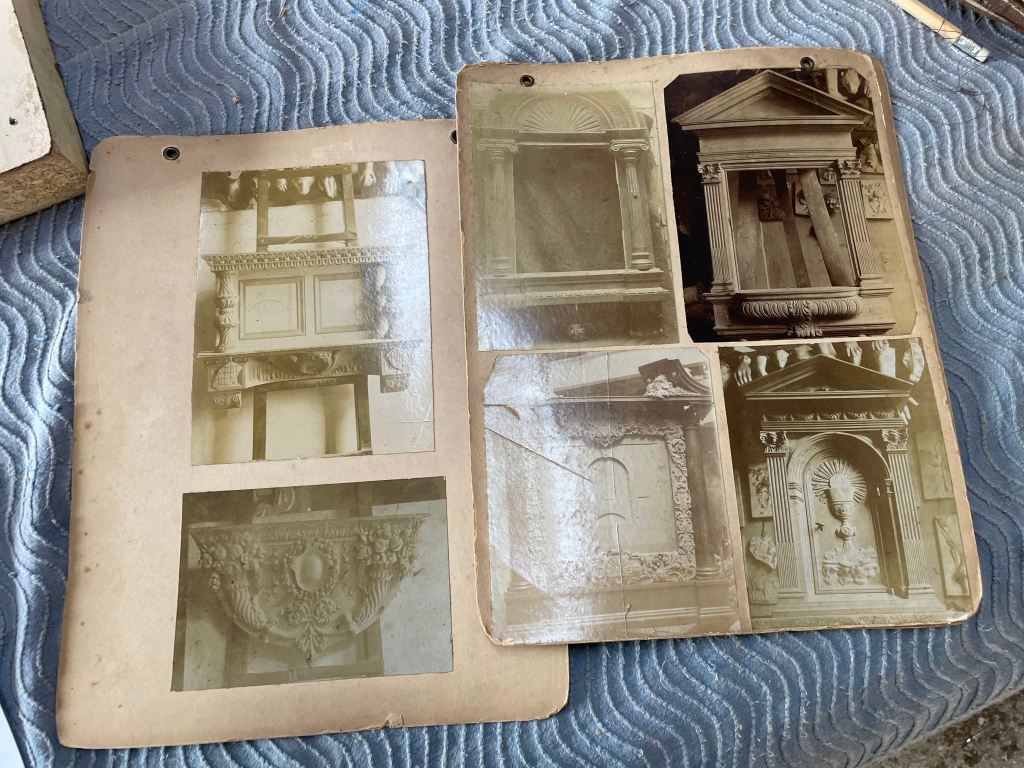

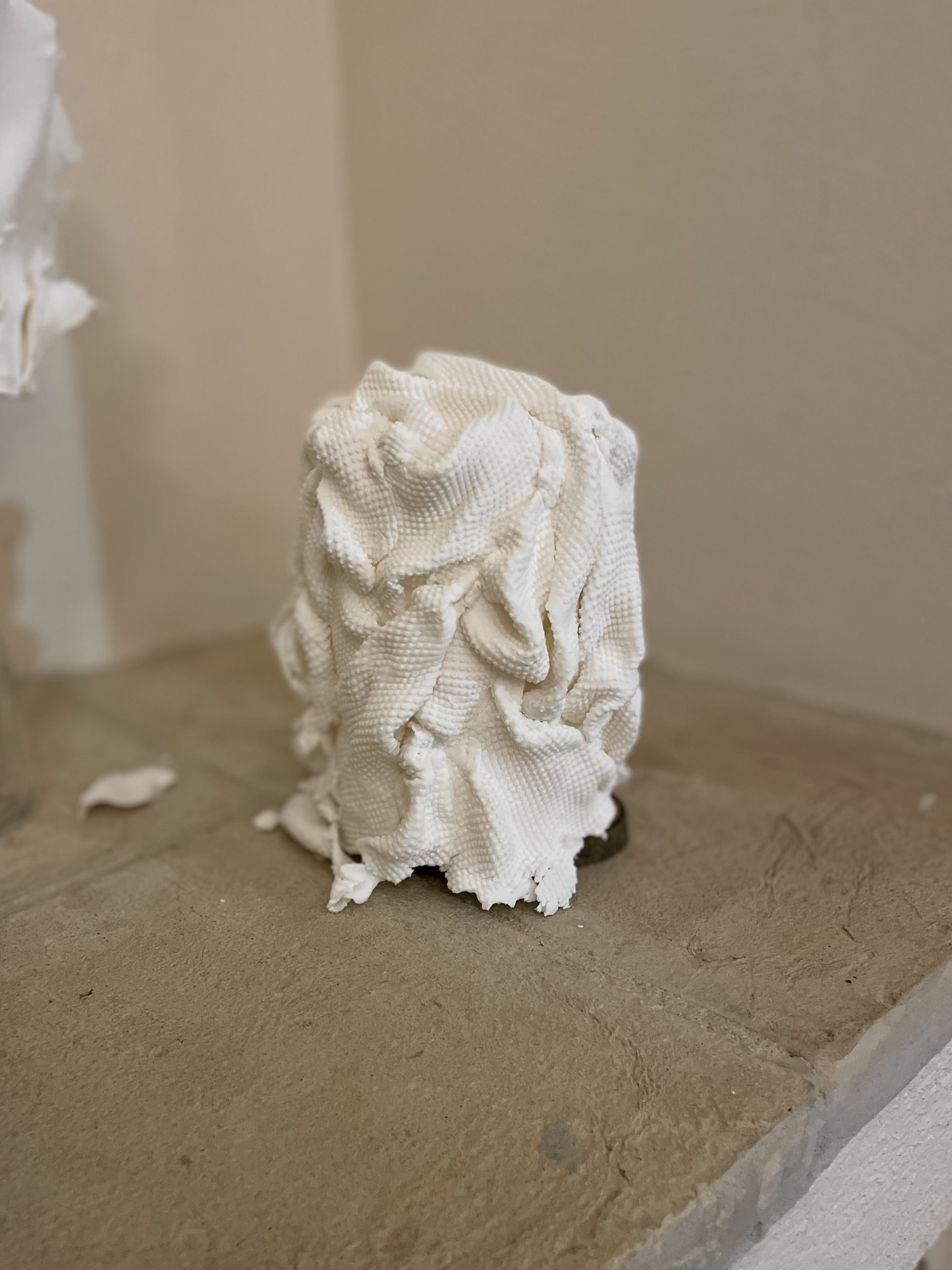

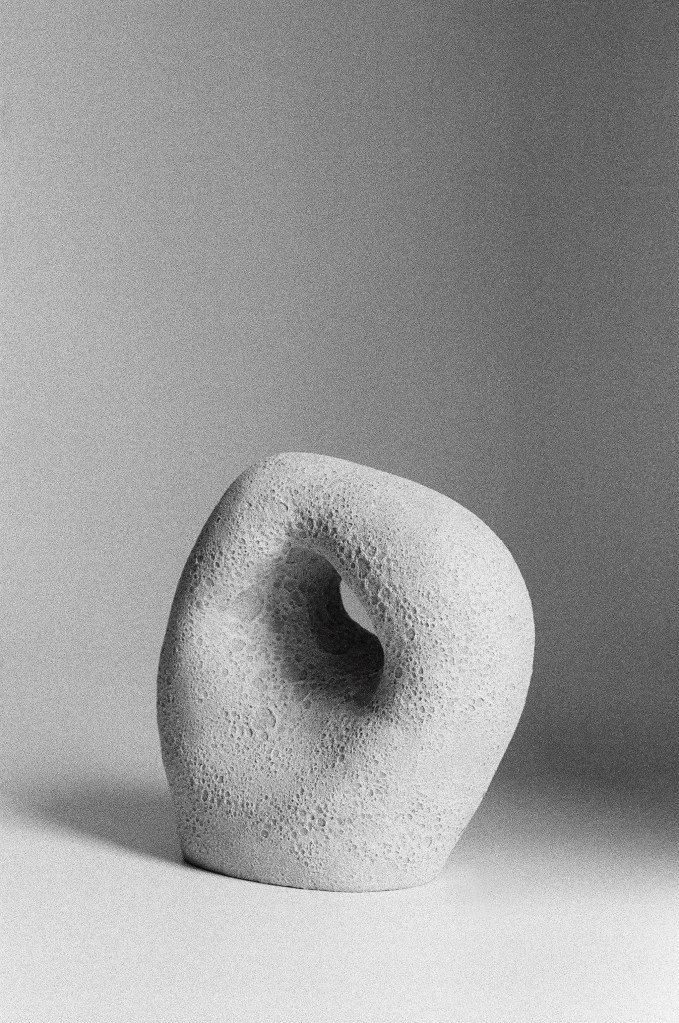

Ceramics of all shapes and glazes have been a source of interest and inspiration to me. Every piece is slightly different and must be treated with care and attention. The passion and work that went into their creation, poured in by the artist, wedged into the clay, demand one to act kindly and respectfully. To observe closely and feel the surface – sometimes rough, sometimes soft and smooth.

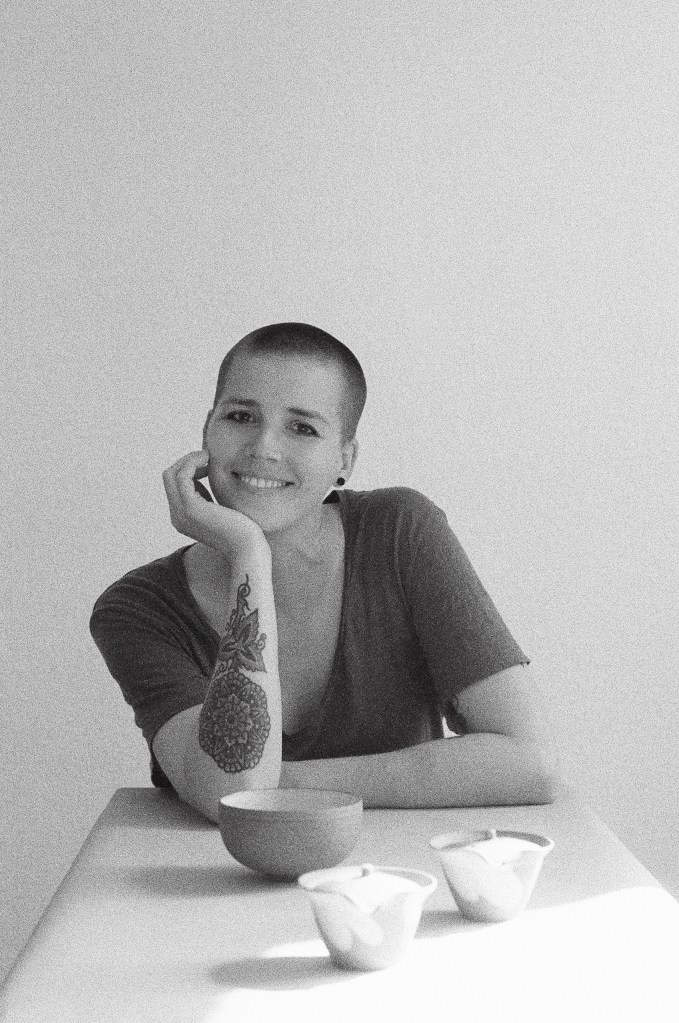

Karina Klages‘ works are particularly enchanting. Her designs radiate clarity, tranquility and balance. I have been wondering about her creative process for a long time. I reached out to Karina and she has kindly agreed to answer my questions.

credits: Karina Klages

Could you please elaborate on your background? What made you chose to work with clay?

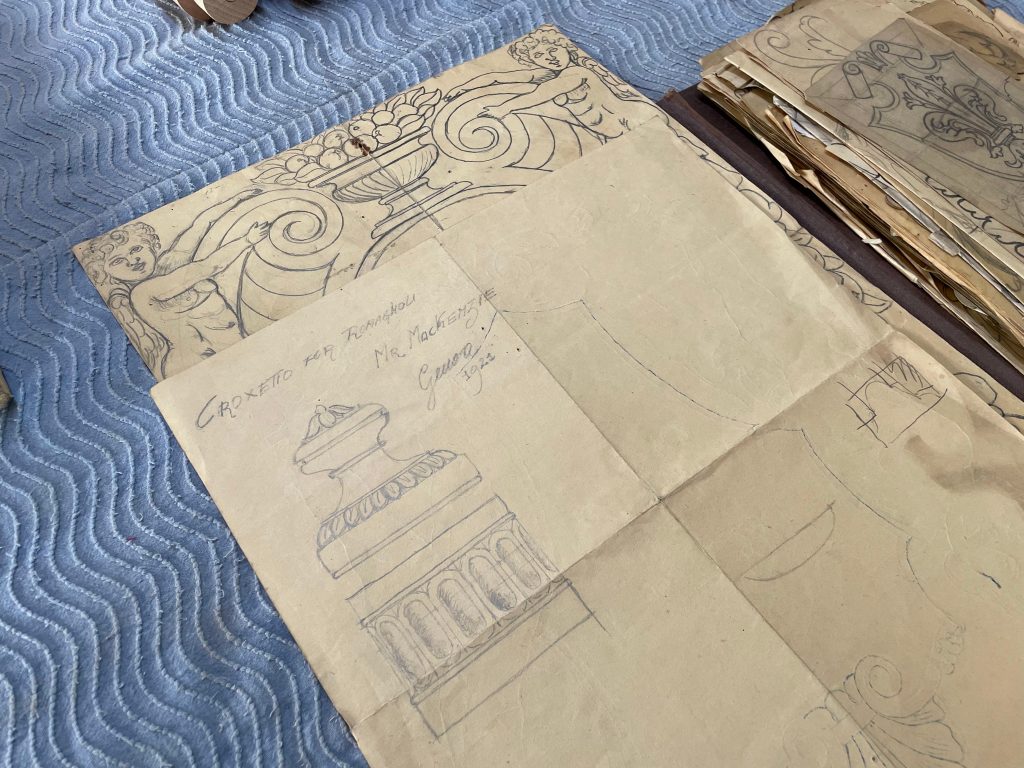

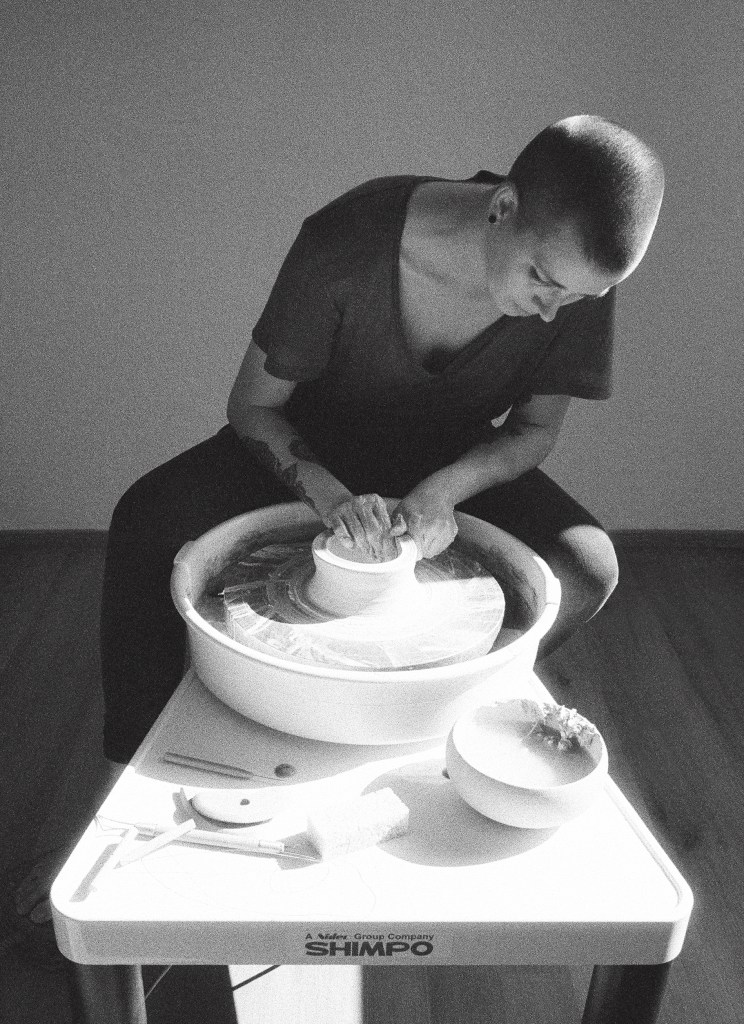

Karina: My sense of beauty and my strong passion for aesthetics led me to the University of Hannover (Germany), where I completed my graphic design studies in 2008. Creativity in many forms is part of my life like the air I breathe. It always came very easy to me and revealed a certain freedom and joy within me. From childhood till now you often found me drawing, painting, creating with different materials. I’m totally in love with film photography also. Since university I worked as a freelance graphic designer and a few years ago I looked for an artistic, manual balance to my computer work and then started creating with clay. I didn’t plan to sell my work, this was an organic process – and honestly it does not feel like a new „business“ at all, but like a new medium to transform what I have in mind. In a secret way clay completes me – more than any other material in the past. And I feel a strong shift into new creative ideas, they are pretty endless. It came slowly but steady that I feel more as an artist now, than a designer.

As far as working with clay goes, I’m using my artistic background and education to educate myself here. I read a lot, watch videos about techniques, observe other artists, buy ceramics to explore techniques and learn from them. This is all an important process for my work – even if I often feel like I’m making slow progress.

Through highs and lows I give myself the freedom to be a learner – and that makes my paths exciting and adventurous.

Do you experience different stages in your work? How do you feel confident with your designs?

Karina: Sometimes I work over weeks on techniques or sets of tests that I can’t complete successfully and that don’t produce the desired results. These times are sobering. But then it turns out that months or even a year later I can use this experience for further work. Failures and ideas combine to form new paths. Everything is a long process and also a lifelong journey, I think, to give expression to one’s own inner voice. Through highs and lows I give myself the freedom to be a learner – and that makes my paths exciting and adventurous.

Please walk me through your design philosophy & process. How does the Japanese concept of Wabi-Sabi inform your work?

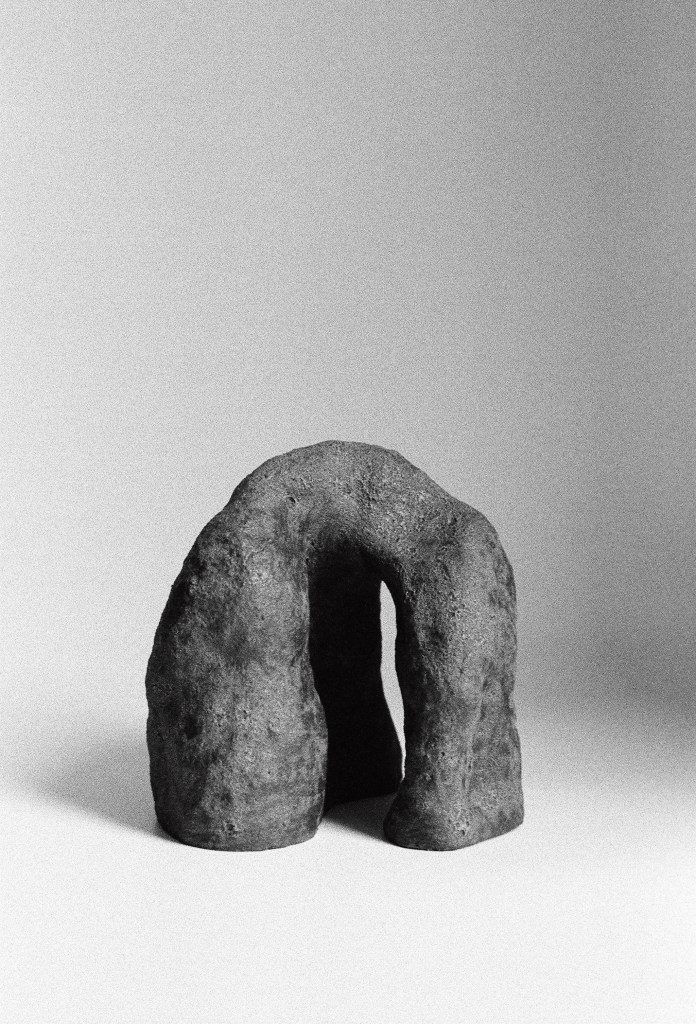

Karina: I would name authenticity as a key philosophy. This topic drives me. I want to be and live authentically myself – and my art should also radiate this. I’m looking for the real, the true, the beautiful. This can be expressed in many ways, in many different forms and I love to follow the flow. Trying out different ways and techniques is very educational and I can find out along the way what it is where I am most drawn to creatively. For me working with clay is also very spiritual. It was that special moment in my life where I was struggling with loss and brokenness when Wabi-Sabi’s aesthetic concept resonated with me strongly. I was looking for the real and for the truth and found it also in the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic at that time. I saw it in great Japanese teaware and in pieces that came out of wood firing kilns. I was blown away by its beauty and imperfection. Nothing is disguised here to make something apparently beautiful, there are no masks here – on the contrary – the old, the broken and the imperfect are seen as beautiful. There is a subdued but also fertile beauty. A beauty of impermanence and a beauty of maturity. These images and feelings became a deep inspiration for my work.

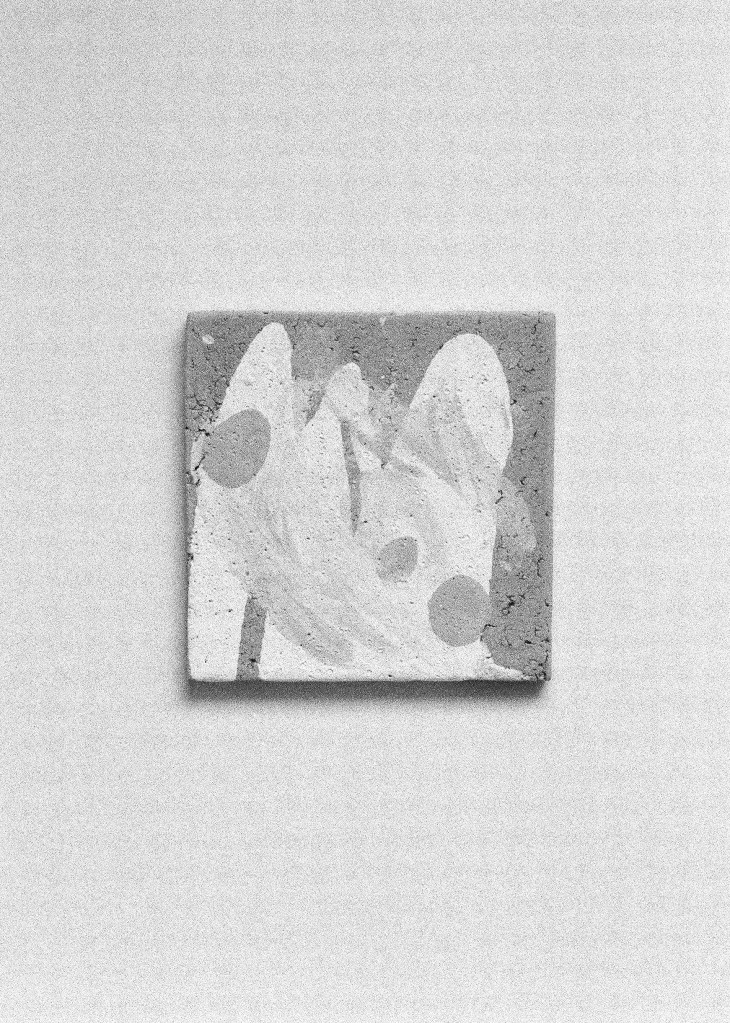

Till now I love to work with rough surfaces the most. But nevertheless I feel more color for my work in the future and I think that some new perspectives are developing in myself. At the moment I do a research and some tests about the technique Nerikomi. I often feel that I’m not there where „I want to be“ – but honestly I cannot name this final „goal“. It is just an inner longing to work on, to try new things and to grow. To grow my inner artistic voice even more.

Credits: Karina Klages

How do you differentiate between sculptural works and works that serve a practical purpose?

Karina: I recently read about the thesis that the boundaries between applied and fine arts seem to be becoming more fluid again. Applied artists work more and more freely, while the others like to take on the craft. I often find these boundaries to be fluid. Of course, there are some of my pieces that are objectively intended to be used, but I don’t want to see them just as useful objects, but as something that has a certain artistic value, so that they can also be perceived as a “work of art” in their own right. In this way, vessels that are created more freely can certainly acquire a sculptural character. Pure sculptures are works that serve no purpose other than to be viewed. I am working on all these forms of expression and when the time is right I will show more of them.

I really appreciate working with the freedom to design individual pieces. I’m most comfortable with this idea, even though some things may be similar or repeated in a similar way. I could never get used to the idea of bringing out collections on a regular basis. When series are created, they should grow entirely out of freedom and the moment.

It is a great privilege to be able to work with a raw material from this earth.

What materials and techniques do you work with & why?

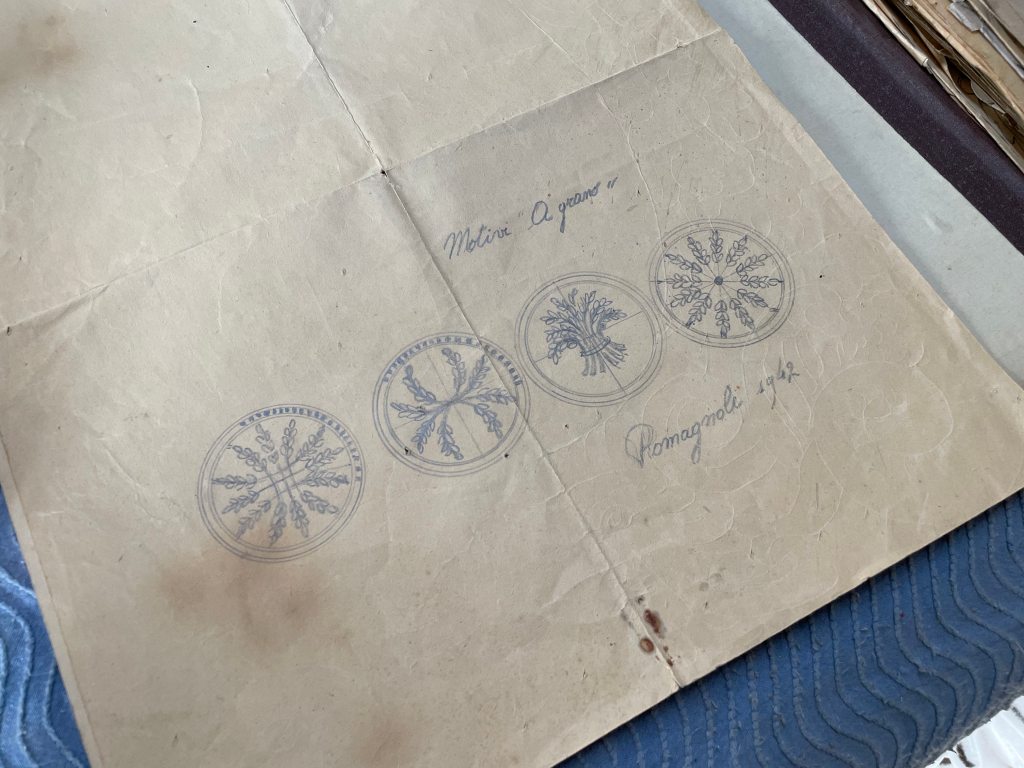

Karina : It is a great privilege to be able to work with a raw material from this earth. Clay is a weathered layer of rock that is taken from the ground. It is a product of the past, will be processed by me in the present and will survive as a fired vessel in the future. That is why it is very important to handle this material mindfully. I work with „Westerwald“ clay from Europeans biggest clay mining area located in Germany – it is perfect for any use.

What glazes do you use?

Karina: Over all I love to work with raw surfaces the most. If I would have the opportunity to unlimited knowledge from master potters and unlimited access to wood firing kilns I would prefer that 😉 – but for now I fire with electric kilns. I sometimes use commercial and self mixed glazes when I find their outcome could please my idea on the ceramics, but in general I’m looking for ideas to „paint“ the clay without using any glazes, to go further with rough surfaces. I’m a big fan of more natural tones and natural surfaces.

How do you feel about failure?

Karina: The whole process of working with clay is a big journey of failures and takes a lot of patience to go on. I totally understand, when someone is quitting her/his clay journey at that point. The production of a piece alone takes up to several days or weeks to await the drying stages. When the firing finally takes place and the glaze gives an unexpected/bad result at the end, then you have sometimes wasted a lot of time. Here you have to be patient, persevere and just keep going.

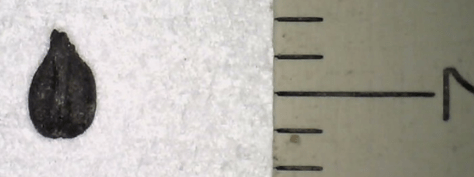

Shiboridashi. Credits: Karina Klages

What role does tea play in your work?

Karina: My first association with tea came from a graphic design job creating a corporate identity for a Japanese green tea label. I remember the day we photographed all the different teas and then got to taste them cup by cup. This was a nice and new experience. After that I started drinking tea and when I started working with clay, the first thing I wanted to realize was teaware. To this day tea ceramics are a big source of inspiration for me.

I started with an idea of a Shiboridashi und repeated it many, many times to find a useful and aesthetic shape for me. Over the time it developed more and more (and still will). Afterwards I started with Gaiwan forms, different cups, tea bowls and tea pots. And all these forms still change and grow to a better version every time.

When does a piece feel finished?

Karina: Recognizing when a piece is finished is not always easy – but I can feel it. Often I can recognize that at a certain point in time, with certain knowledge, a certain result can be obtained. I try to accept that. Of course I’m evolving and looking back I don’t like my old pieces that much anymore – but I know that at that time I made a positive decision to sell the ceramics. So I acknowledge my decision and know that I will continue to develop over the years. That is a normal process for every creative.

Credits: Karina Klages

What do I like and what not? Which technique, color, surface do I want to continue with? Do I like the aesthetic?

What other artistic practices to you pursue? How do they inform your pottery?

Karina: I find it helpful to work with different materials in parallel with the clay, so I can make different sketches/ideas and incorporate them into my work with clay. I also prefer to be open to art in general, to find new inspiration and to expand my work with incentives, techniques, colors and shapes. Important is to be brave and to play, experiment and outline any idea. The key is to work. If you work, it will lead to something. And then the decision-making process is always there: What do I like and what not? Which technique, color, surface do I want to continue with? Do I like the aesthetic? If not, then I keep experimenting until an inner voice agrees with what it sees.

How would you like your work and pieces to be understood?

Karina: I like the idea of very unique pieces. I like the idea, that every customer/collector choses the pieces that resonates with her/him. And I want to look them on my ceramics as art pieces – even if they can „use“ them in their daily life. I don’t want to be perceived as someone who produces masses of identical objects – because the world has enough of that already. I want to trigger a differentiated view and make aesthetic demands on my work.

Beauty is always found where truth is found. As an artist/creator/designer I always want to follow the path of making the practical beautiful. After all, who likes to use objects that aren’t beautiful? Rather, we should always surround ourselves with beautiful things in everyday life, because they make our hearts smile. We then use objects with more mindfulness and joy – in this way we honor the object and the time and love that the creator put into it.

Gaiwan. Credits: Karina Klages

How does it feel to let go of the pieces?

Karina: The artist enters into a special connection with his material and his work of art. This process is important and happens silently between the artist and the object. This is where the final expression forms. The artist puts in everything that is necessary to follow a certain aesthetic image. When I finish an art piece, it belongs to the people. But the inner secret process always belongs to me as an artist. I really love to feel when a piece is ready and when there is a buyer who resonates with this special piece – this is pure joy.

When I finish an art piece, it belongs to the people. But the inner secret process always belongs to me as an artist.

What sources & books do you recommend for aspiring potters?

Karina: I recommend every young creative to use Instagram as a platform to get started. Here you will find everything about art, orientations, techniques and a variety of artists. Many potters have already written books about their work, so you can buy a book right away, which also corresponds to the style you prefer. I have found books by Melissa Weiss, Stefan Andersson, Phil Rogers and John Britt to be very helpful for my own learning. I also love to watch different artist statements (mostly by Goldmark Gallery on YouTube).

You can find Karina Klages’ beautiful works via her online shop or Instagram.

Thank you very much, Karina, for giving such a detailed insight into your work!