credits: jasmine rae

About two hours from Florence, I leave the highway to follow a rough, stony little path up the hill. I am close to the town of Chiusi, at the border of Tuscany and Umbria. Left and right to the road, fields stretch out widely. On top of the hill, I can already spot grand villas framed by cypress trees. It is a rainy and windy day, the landscape presents itself with beautiful sobriety.

I’m on my way to interview Jasmine Rae, a well-known fine art cake designer from San Francisco. Jasmine is in Italy to host a one-week workshop organised with Strada Toscana. The small group tour company creates retreats, workshops, and tours in Tuscany and Umbria. I have been following Jasmine’s artistry for a long time, enamoured with the way she captures calmness, potent persistence, and dynamism in so many different shapes and tastes. Her treatment of materiality, texture, and surface moves me. When I finally arrive at the 17th century villa, the stormy weather ploughs boisterously through the grass and leaves. The wind creates shapes in nature resembling some of Jasmine’s most dynamic cakes.

Jasmine is a self-taught cake designer who redefined beauty standards in the wedding cake industry. Trained in a variety of arts, including murals and filmmaking, Jasmine always had artistic inclinations. However, dough, creams, and mousses were not her preferred media of expression: “It’s not that I chose cake.” In fact, Jasmine studied cognitive science (B.A., 2003) and psychology (M.A., 2013). In 2005, Jasmine’s boyfriend at the time was captured by the idea to set up a professional bakery. His entrepreneurial spirit was contagious and inspired Jasmine to start a wholesale bakery. They scrounged in the vaults of craigslist to find enough used equipment to build out a tiny commercial kitchen in the belly of an artists’ building. Opportunities of the business soon turned into cake making, and about four years in, she quit wholesale altogether to just focus on cakes. It was a risk, energised by enthusiasm and her self-proclaimed ignorance of what it takes to run a viable business. The artist community around her encouraged her to return to her creative roots as she experimented and learned on the job.

To pick up the craft and chemistry of cake baking, she took weekend classes for hobby bakers, but mostly practiced on the cheap with her clients while she was learning: “I made so many mistakes, it was kind of an uphill battle learning the science and the baking.” Whenever she felt exhausted, discouraged or empty, she was held to the job because of future obligations, “because of the way it works.” With bookings made many months ahead, it was impossible just to stop one day. Jasmine remembers how she was “forming [her] own boot camp”. The hurdles she had to overcome let her develop expertise and persistence. Right from the start, she liked to modify recipes and mess with conceptions of beauty. Her early cakes already showed a hint of her future styles: “my first cakes were unlike any cakes I had ever seen yet so poorly executed because I was completely unexperienced.” Jasmine had to build her technical foundations first to push forward her design vision.

After eight years, I reached this place where everything kind of coagulated for me, and I really found freedom in the work that I was doing.

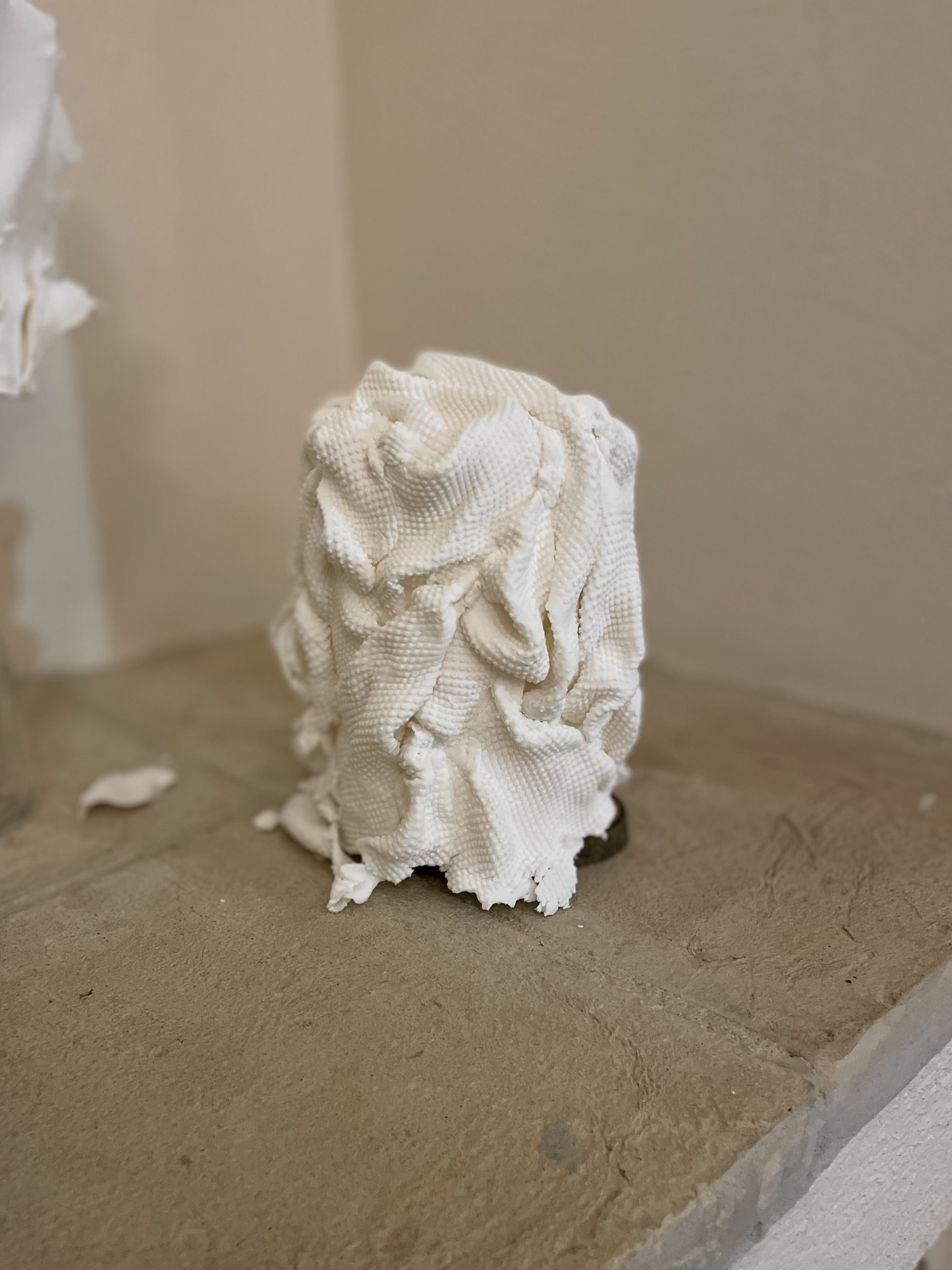

While the art quickly made its way into her work again, it took several years before cake making and her artistic visions could combine fully. Mastering the techniques, styles, and business aspects required for her young bakery, Jasmine slowly began to enjoy the process: “I was in the practice of it, and then the desire started to build as the practice became more and more satisfying.” It was about eight years into the job when she recalls finding “a sense of self as an artist and a cake maker”. Working in a low-humidity environment in San Francisco, the fondant she worked with would dry up quickly. It was challenging to create the smooth, silky surface that was desired for wedding cakes at the time, and that was understood as particularly skilled: “the smoother, the better”. Her fondant, instead, would crack and crumble, “and it was called, with disdain, elephant skin. It was not appreciated, it was seen as a flaw in cakes.” However, “year eight was kind of the moment that I was like, you know, f* that, I love elephant skin.” Jasmine laughs. Not only did she dare to appreciate elephant skin as beautiful. She began to let her fondant crack purposefully. She told and taught the world about the beauty of cracked, uneven, dried up fondant: “And that was when I really found freedom.”

credits: jasmine rae

Jasmine’s design philosophy is based on what she calls the “natural process”. This process comes forward as she builds a relationship with her materials. She explores and facilitates the structures, textures, and surfaces that are inherent to a specific material and its exposure to different environments. Then, she allows the material’s characteristics to guide the final cake design: “all you can do is influence, but you can’t control the outcome of it, and so for me, that’s the natural process.” When she creates cake decorations with rice paper or uses the technique of fondant marbling, she bows down to the curves and folds that are forming. She then explores their potential to create movement or stillness for the overall composition. It is an approach based on acceptance and asking: “What did form? And saying, that’s really beautiful. I love this part right here that’s doing this. I’m going to pick this up and put that on a cake and if it starts to fall or melt in certain ways, how can I appreciate that and enjoy it or continue it? What lines did it form such that now I can start to bring the action in this direction and guide the eye around the cake in that way?” In this manner, Jasmine builds a “relationship with what is happening”.

Asked if she sometimes sees a texture in nature that she would like to emulate, Jasmine nods. However, instead of merely copying visual characteristics, she inquires into the process that creates a specific surface or object. To form a bark-like texture for a cake, Jasmine would refrain from using a mold. She asks: “How did the tree develop that? Is there some way I can almost recreate that process in order to get the look of it versus recreate a look by just duplicating it?” She believes people are sensitive to mere copying and spot the artificiality created by repeatedly using a mold. The natural process is much more pleasing to the eye, as humans are created similarly. Jasmine wants us viewers to see and feel the natural process in her cakes as the natural selves we all are.

I am really very interested in making the relationship to my material which I think is the definition of a natural process. An unnatural process would be to design every single detail and say it’s this many flowers and this is symmetrical with that […] I’m not interested in that, that feels deadening inside.

How does Jasmine explain her approach to cake design to clients? How does she communicate the liberty she takes in interpreting their wishes? When customers come to Jasmine with a particular cake inspiration, she lets them know that the final cake may not look at all the way they imagine it: “I don’t commit to my clients that something is going to look a particular way.” How does she combine her artistic inclination with serving her clients’ wishes? Jasmine responds: “The work that I do with clients is less about telling them who I am and how I work and more about asking them to describe to me how they feel. That’s where the psychology part really aids me in my work because what they are responding to when they look at this cake, that’s inspiring them […] what they are responding to is really the way that they make themselves feel when they look at it. So, if I can get them to share a little bit about that feeling, that’s the pathway […] I can design from their feelings.” Jasmine sketches 90% of her designs on the spot while her clients taste the different cake combinations. When it comes to cake flavours, Jasmine does not have a set selection: “It’s part of how I keep it feeling alive. It’s important for me not to have a menu.” Jasmine herself loves citrus flavours, other acids, dark caramel, in contrast with herbs, flowers, creamy textures, and dark chocolate. She takes pleasure in bringing unexpected tastes to her customers: “I love seeing clients surprise themselves […] they pick the things that they think they will like the most. And they don’t even know what they don’t know.” Jasmine’s clients usually enjoy the creative energy she radiates and entrust her with a lot of creative freedom.

In addition to her custom cake designs, Jasmine teaches workshops all over the world. She has been giving courses in New Zealand, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, Canada, a range of places in the United States, and now Tuscany. It is the first workshop she has organised together with Strada Toscana. The company reached out to her in 2019: “for me, it was really exciting. I’ve never heard of a cake maker having a retreat workshop. So, there was a lot of possibility.” The workshop consists of instruction lessons and cultural experiences, including trips to the cities of Pienza, Città della Pieve and Chiusi and a visit of Mulino Val d’Orcia Spedaletto, a family-run organic flour mill. Participants also tap into local culinary traditions with chef Lorenza Fontebasso teaching the group about Italian herbs.

The retreat is based in a beautiful 400-year-old villa with a spacious garden. The rich landscape is used for outdoor sketching. One large room is dedicated to Jasmine’s instructions, and I am lucky to witness a workshop on wiring rice paper. On a long, wooden table I can spot edible colours, fondant, and a range of cake making tools. In the back of the room, the results of previous instruction lessons show the impressive creative energy of the group. The participants exchange their experiences with rice paper and begin exploring the material. Jasmine walks around and inquires into their decision-making. She tries to hone in on what part is interesting them most and help them recognise how their perspective is unique. The atmosphere of the room is cosy and intimate as the daylight is slowly giving way to the darkness outside.

I try to give very little instruction because I don’t want to emphasise that there is a right way to do anything. I try to give them just enough instruction so that they are not terrified to start but not so much that they feel like ‘I have to do it this way.’

With the workshop, Jasmine aims to aid her students in developing their artistic voices. Her participants are all well-experienced cake makers, and Jasmine does not teach specific skill sets. Instead, she uses different techniques to access the quest for self-expression. She leads the lessons with very little instruction and tries to leverage what her participants already know, “such that they can see who they are as an artist, do more with it and feel aliveness and start little tendrils of possibilities with the skills that they already have.” One exercise focused on using just one single tool to create the whole decoration of a white fondant cake: “when you constrain that much, you define the play area, and then people really go crazy.” Her students had to push their creative boundaries, asking themselves, “What can it do? Could I use the handle?” Jasmine reflects with excitement and contentment: “They were surprising themselves constantly.”

It helps us know ourselves better when we see other people making different choices.

One pathway to find your voice as an artist is communal reflection. Jasmine tells me about another workshop session, where every participant had to shape and add a piece of fondant to one shared cake: “we would all be watching and observing, like, how are you doing this? If I see you putting this piece on right here, how does that feel inside of me, is that the same choice I would make?” Jasmine points out: “It helps us know ourselves better when we see other people making different choices.” During this session, one participant handled the fondant so much that it began to dry out. Jasmine refrained from over-instructing and allowed for the natural process to appear. She did not warn her student that the fondant would soon start to crack. And so, it happened. Once the participant tried to apply her fondant piece to the cake, it broke into pieces. Jasmine recalls the experience with joy: “It’s such a great moment when that happens because then she’s having to solve it. […] She ends up composing a whole new shape […] that was not her original design.” Jasmine pushes her students to give space for the natural process and to honour its path and effects: “we talk about, can you accept that? Can you stand for the beauty of what you’ve just created? Can you still say, I love this, it’s beautiful, and I’m going to show you, too, that it’s beautiful?”

I love doing workshops because I get the mirror and the reflection and the reminders in the students and where they are in their journeys about what it is continuing to take to develop.

…

Driving back home to Florence, I feel a profound sense of sincerity. Jasmine’s courage to try out different techniques and textures for her cakes and loudly declare the beauty of cracked fondant is energising. I ask myself, could I disrupt the status-quo by exploring a new way of seeing? And could I then speak up for the beauty of the eclecticism, the wildness, and calmness that emerges once you unleash your emotions onto your environment? Could I bow down, give space, and admire what happens when I, sincerely, just let it happen?